Latest Posts

Lansdowne facilitates at Movin’On

What will mobility look like in a sustainable society?

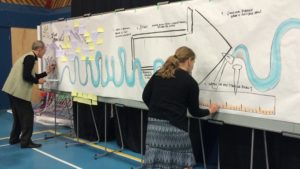

Lansdowne is thrilled to have had the opportunity to support the advancement of the global dialogue on the future of mobility at Movin’On this week. Movin’On is the new edition of the Michelin Challenge Bibendum, bringing representatives from around the world all tackling different aspects of this complex problem: what will mobility look like in a sustainable society? Speakers, scientists, creatives, entrepreneurs, executives and thought-leaders all came together to explore, play and innovate to advance this key global issue.

Fiona Wright joined the C2 facilitation team to support the following workshops and masterclasses hosted by Michelin:

- Safer Mobility: Collaboration between Products, Infrastructure and Education

- Key rec: Segregate infrastructure, build in speed and behaviour limiters to products, provider behaviour motivators through insurance incentives, and normalize regular competency testing (every 5-10 years)

- Key Tech Enablers: making an impact on safer mobility

- Key insights: combining AI and automated sensing with driver control is a key transition step

- Safer mobility for an Aging Population

- Key insights: Planning for driving-retirement is a needed behaviour change. Many seniors get around primarily on their social capital – asking people for rides. There are interesting ways to create platforms for even better exchanges and store social capital.

Looking forward to Movin’On 2018!

Why innovation processes don’t always have to be innovative

It was my recent honour to join a power-house team of

facilitators and social innovators at a public sector conference on innovation. The event was held together by a curated set of Liberating Structures, expert insights, practical experiences, and storytellers from the field on their experiences implementing different methods and tools to facilitate innovation at work. Despite the individual commitments of many of the 200 participants present to personally change subtle individual behaviors promoting cynicism in order to make space for something new at work (using TRIZ), as I sit down with my coffee on the second morning I overhear:

“This conference on innovation isn’t innovative enough”.

As a practitioner in the challenging art of creating spaces conducive to liberating creativity in service of seeing things in different ways, I find it interesting to unpack that thought.

What is innovation?

By definition, an innovation is “a new idea that works”.

It’s not just a new idea alone, it has to have an application and be implemented to acquire ‘innovation’ status. That idea can be to simply combine old things in a new way – e.g. how long did we have both luggage and wheels before someone thought of putting them together? ‘Innovation’ status also doesn’t last forever – once it’s not new anymore, is it still innovative?

So, is it necessary to have an innovative process to explore the topic of innovation? In my humble opinion, no. No-one can guarantee that a process will ultimately produce an innovation – all we can do is create a space that maximizes the possibility of one emerging. If a tried, tested and true process meets certain basic principles, we don’t always need to do things differently to get a new result (and don’t get me wrong, sometimes we absolutely do – it depends what we’re doing right now!). The spark for an innovation can come from a variety of sources – not only from something triggered by a new process, but also from a change in the current context, the timing, the mix of people in the room or the readiness of the system at large.

It’s true that some amazing innovations have come from pouring our resources into research and development, from experimenting, from trying things and failing. Flight, for example. Space exploration. Advances in medicine, technology. This is what individuals and the private sector are really good at. I would argue, however, that our public institutions are there to support a certain amount of stability and resiliency in our society – and as such they have a lower risk-tolerance. They cannot (we cannot) afford to risk such massive failures – the consequences are much greater than simply going out of business.

To bring innovation and experimentation into a context like this seems to require one or both of 2 strategies allowing for failures that can be learned from without a failure taking the entire organization out:

- exploring it slowly and carefully from a currently practiced, trusted, stable process; and

- creating a protective boundary around the innovation space within the organization (like a sandbox), thus protecting the rest of the organization from adopting a failing strategy.

This 2 day Innovation conference (using a mix of traditional process with creative, liberating structures) ended with 27 fleshed out and actionable ideas for changes to internal processes, external processes, and public policies and programs – most of which were innovative in general to our times and country and some of which were innovative to this particular context. The Senior Leadership Team had reviewed and revamped their specific commitments to innovation in processes, structures and strategy based on the input of 200 frontline workers and staff in 1 day. While the conference was by no measure a C2Montreal, neither could it have been nor needed to be. It produced a number of new ideas, commitments and action plans that are seeding innovations. I would call that a well-executed success.

Fiona Wright is a Strategic Facilitator with The Lansdowne Group.

Innovation processes: 5 principles

So “something’s not working”… and that ‘something’ is between us and where we want to be. We need something different. Something new. A new idea that works. An innovation.

How does one go about getting an innovation?

What can we do to find that new idea that works? Standing on an innovation and looking back, we see there are a variety of ways we can get there. A spark of imagination. A dream. A systematic cross-pollination of options followed by a rigorous review, prototyping, evaluation, piloting and selection process for the best idea. Shutting a group of young designers in a room with coffee and not letting them out until they come up with something.

With limited resources, which is your best path forward?

Here are some basic principles we use to design a process that evokes innovative thinking:

-

Get the right people in the room.

To turn an adage on its head, if you’re not part of the problem, you can’t be part of the solution. I have been part of many a consultation process that invited a relevant, yet incomplete, slice of those who have a stake in the issue. In particular, the ‘user’ of a potential service or product or systems shift is often overlooked. Whenever there are stakeholders missing from the table, the resulting solution is incomplete and will typically face resistance from those who were not involved, or not be implementable (not ‘work’) because it requires support and/or action from a particular person or group.

Objection: “It would be faster and easier with a smaller group”

Response: True in the short term, but here’s a wise proverb moment: If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.

-

Get people into the right side of their brains.

Use just enough structure to provide constraints such that there is still a space that invites creativity. We can call these liberating structures. We often use a method based on Lego® Serious Play® to bring participants into a place of flow and out of their thinking minds into a place of purposeful creativity.

Objection: “This group is serious about getting things done. They won’t want to waste time ‘playing’.”

Response: Actually all adults like to play when it has a meaningful and relevant purpose. As Plato said, you can learn more about a person in an hour of play than in a year of conversation. Our bodies hold a lot of information – when we can include the wisdom of the body and heart with the wisdom of the mind, we can access deeper levels of insight. We have used Lego® Serious Play® with executive teams in the federal government, large private sector companies, small to large non-profit organizations as well as a number of law enforcement agencies at the local and national level, and accomplished more work than typically expected for the time committed.

-

Isolate people in a space outside their usual environment.

The importance of this is routinely underestimated. Being outside of your usual environment typically elevates your focus on your surroundings and therefore helps you be present to what is going on right here, right now. Your nervous system is slightly more activated since it doesn’t know what to expect. This helps you to be in a state that is more agile than when you’re in your usual routine / habits / patterns.

Objection: “It’s easier and cheaper to just do it here”

Response: A one-day workshop for 10 people is 750 hours of employee time. In relation to that investment, the cost of a different location is typically much less significant. It is more expensive to have people only half mentally present, stepping in and out, or covering only half the ground.

-

Work on things that matter to people.

Meaning, pain and passion are the fuel and the drivers of innovation. Working on a question that doesn’t really matter to people typically won’t ignite anything new – the spark isn’t there. Sometimes we find that what we think is important, isn’t actually what matters.

Objection: “We need to address this particular issue, we don’t have time right now to work on other things.”

Response: If you can link your issue to what matters to people, you will get more energy and remove blocks to the problem.

-

Zoom out. Look at the system. It matters.

There are many ways to model or visualize a system:

- in 2 dimensions using systems mapping such as flow or causal loop diagrams, rich picture maps, icebergs, or social network analyses; or

- in 3 dimensions using 3D modelling tools such as Lego® or dynamic mapping.

Objection: “We all know what the problem is. This systems mapping is confusing and takes up too much time.”

Response: We often think we’re on the same page, but the majority of the time we see things slightly-to-very differently. Even if we have the same idea of the problem, the best solution will hinge on a shared understanding of the current reality of the system.

The process of building a model of the system together typically unearths unspoken assumptions, mental models and allows a convergence of perspectives in a group. Only when we see ‘what is’ without judgement, do we actually have the possibility to shift things to what could be.

What other principles for innovation processes have you found helpful for complex challenges? Please comment below.

Fiona Wright is a Strategic Facilitator with The Lansdowne Group.