Why innovation processes don’t always have to be innovative

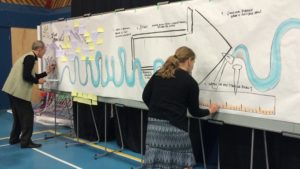

It was my recent honour to join a power-house team of

facilitators and social innovators at a public sector conference on innovation. The event was held together by a curated set of Liberating Structures, expert insights, practical experiences, and storytellers from the field on their experiences implementing different methods and tools to facilitate innovation at work. Despite the individual commitments of many of the 200 participants present to personally change subtle individual behaviors promoting cynicism in order to make space for something new at work (using TRIZ), as I sit down with my coffee on the second morning I overhear:

“This conference on innovation isn’t innovative enough”.

As a practitioner in the challenging art of creating spaces conducive to liberating creativity in service of seeing things in different ways, I find it interesting to unpack that thought.

What is innovation?

By definition, an innovation is “a new idea that works”.

It’s not just a new idea alone, it has to have an application and be implemented to acquire ‘innovation’ status. That idea can be to simply combine old things in a new way – e.g. how long did we have both luggage and wheels before someone thought of putting them together? ‘Innovation’ status also doesn’t last forever – once it’s not new anymore, is it still innovative?

So, is it necessary to have an innovative process to explore the topic of innovation? In my humble opinion, no. No-one can guarantee that a process will ultimately produce an innovation – all we can do is create a space that maximizes the possibility of one emerging. If a tried, tested and true process meets certain basic principles, we don’t always need to do things differently to get a new result (and don’t get me wrong, sometimes we absolutely do – it depends what we’re doing right now!). The spark for an innovation can come from a variety of sources – not only from something triggered by a new process, but also from a change in the current context, the timing, the mix of people in the room or the readiness of the system at large.

It’s true that some amazing innovations have come from pouring our resources into research and development, from experimenting, from trying things and failing. Flight, for example. Space exploration. Advances in medicine, technology. This is what individuals and the private sector are really good at. I would argue, however, that our public institutions are there to support a certain amount of stability and resiliency in our society – and as such they have a lower risk-tolerance. They cannot (we cannot) afford to risk such massive failures – the consequences are much greater than simply going out of business.

To bring innovation and experimentation into a context like this seems to require one or both of 2 strategies allowing for failures that can be learned from without a failure taking the entire organization out:

- exploring it slowly and carefully from a currently practiced, trusted, stable process; and

- creating a protective boundary around the innovation space within the organization (like a sandbox), thus protecting the rest of the organization from adopting a failing strategy.

This 2 day Innovation conference (using a mix of traditional process with creative, liberating structures) ended with 27 fleshed out and actionable ideas for changes to internal processes, external processes, and public policies and programs – most of which were innovative in general to our times and country and some of which were innovative to this particular context. The Senior Leadership Team had reviewed and revamped their specific commitments to innovation in processes, structures and strategy based on the input of 200 frontline workers and staff in 1 day. While the conference was by no measure a C2Montreal, neither could it have been nor needed to be. It produced a number of new ideas, commitments and action plans that are seeding innovations. I would call that a well-executed success.

Fiona Wright is a Strategic Facilitator with The Lansdowne Group.